Help keep The Curb independent by joining our Patreon.

Filmmaker Ivan Sen is a one-man shop, writing, directing, shooting, scoring his films from Mystery Road and Goldstone, to the new sci-fi Hong Kong shot Loveland. But, don’t call him an auteur.

In this deep dive discussion, Ivan talks about his search for connection, working with screen icons Hugo Weaving and Ryan Kwanten, and bring the neon lights of Hong Kong to the outback in Goldstone. Through Ivan’s eyes, he transforms the world, and does so with a unique vision. Keep reading to the end to see which city he has in his sights next.

Loveland is out in Australian cinemas from March 17th, and as Ivan requests, please head along and support it in your local cinema if you can.

Thanks for giving me the time to have a chat to you about Loveland and your body of work. I’m super keen to see what you’ve done here with this whole different landscape. It’s going to be very exciting.

Ivan Sen: Great.

It is a bit of a step away from my past work. It’s going from these rural landscapes to the opposite, you know, mega metropolis in science fiction and the future. The people who have seen the film, they said it’s still so different, but still feels like a film that I made, an Ivan film. In saying that, it’s been over ten years work in progress. And I actually started writing this film before I started other films like Toomelah and Mystery Road and Goldstone. This film actually comes before them in the order of things.

Oh wow.

IS: It’s been with me for over ten years. For me, it’s not a huge departure at all.

Is this a continuation of Dreamland? Are you trying to make a trilogy? Or are they associated by similar titles?

IS: Dreamland‘s a strange thing because it could be classified as a sci fi but it’s also set within the contemporary time. But it’s also a film I haven’t actually finished and so I made a version of it and then I pulled it back from being released. I felt like it wasn’t quite… it didn’t quite hit what I wanted it to. The story and thematic elements didn’t quite hit where I wanted them to hit so I have held it back. I’ve actually rewritten the whole project, the whole film into a much bigger, wider work which I’ll get to in the next year or so hopefully.

I’ve seen pretty much everything you’ve done except for that one. I was like, “Oh this feels like a lost gem that I need to visit and see”. And then reading about what it is, it sounds even more exciting and interesting, because it’s so different than what you’ve done elsewhere. I’m keen to see what you do with retooling the story.

IS: It’s something that needs the right actor in it. I’ve learnt a few things over the years. And I think the more creative you become, the more you kind of rely on the right talent to portray the story, the character, and to give it a wider kind of stage.

That makes sense. Do you buy into the auteur theory at all? Because you have your hands over everything, the writing, the direction, cinematography, the composing, the editing, so it is solely your project. Do you consider that when you’re establishing a new film?

IS: No, not at all. I’ve always felt filmmaking for me is just like photography, which I come from. Or it’s from music, being a musician, or it’s similar to being a painter. I haven’t really painted in my life but I just see that it’s something like that. The auteur thing I don’t really buy into and I think the term gets thrown around pretty easily. A lot of directors who are considered auteurs, their work is very strongly created by the team that surrounds the director, and there’s a lot of influences that go into that work from the crew.

I don’t really call myself an auteur. I just enjoy the whole process from all the elements of the process. And for me, I don’t think I could actually go through the whole struggle to make a film if I wasn’t actually getting my hands dirty. And I enjoy that. It’d be like planting a garden or something. You enjoy it because you get your hands in the dirt. And I enjoy getting my hands in the dirt and getting dirty and I’m not sitting behind three TV screens with a suit on drinking a cup of coffee. I’m right in the frontline with the actors and reveling in that space.

Where does the first aspect of film come from? Is it in the script? Or has there been instances where a score has come to you first?

IS: Not really. Well, yeah. It can happen kind of at the same time, but usually I get the story from the land, from the location, and the location will grow the characters. The characters will come from their location which comes from pretty much from observing real life. You have a location, and that location has an influence on the people that live on that location. And it actually defines the characters, because that location has all kinds of elements to it which impacts the characters. And so for me, I think like I consider locations like countries.

For me, even Hong Kong, all I knew twelve years ago is that I wanted to make a film in Hong Kong. I didn’t know who the characters were or what the story was. But I just knew I wanted to go to that place and let a story come to me, grow out of that location. I’ve created music before I’ve created the actual story before and it’s helped. You listen to the music and then that helps the story grow. But pretty much it’s the location that’s given them. And I think that’s why in the end, in the product in the film, if you get a strong sense of the location and/or the place, it’s because that’s where the whole thing started.

Tell me about the first time that you visited Hong Kong. What was your impression there when you first ever visited there?

IS: What blew me away was the energy. Because I remember booking hotels and I found some hotel that wasn’t on Hong Kong Island, but it was on Kowloon side. And I thought, “Oh maybe that’s not a good idea” because I want to be in the thick of it on Hong Kong Island. I just felt like it’s probably some place that shuts down when the sun goes down. And when I got off the plane and got in a taxi and drove through Kowloon, I was just blown away by the energy, the lights, just the overall… I don’t know, just what you’d call the mise-en-scène of the place. It just blew me away and I just couldn’t believe the energy that was going on in all the small streets, in the alleys, driving across intersections and looking down the laneways and just seeing the life force.

And I just got so excited because it’s not from my experience, (my) immediate experience to see that extension of energy and life force which just keeps going and going and doesn’t drop away to darkness like it does here in Australia. Cafes close at two in the afternoon and everything shuts up shop. But over there, things open a bit later, probably ten or something in the morning but it goes, goes well to midnight. And that just got me going, I was so inspired by that life force and energy and that will of people to move and to live life.

Here, people run away to their houses and close the doors. But in Hong Kong, the houses are so small, they want to stay outside anyway. So over there, it’s the life and to a degree you find this throughout Asia, and also mainland China as well, but Hong Kong is specific, it’s got this energy which is hard to find anywhere in the world.

Well, that’s what I found in my travels throughout Asia at nighttime (being) pushed out onto the streets because that’s where the food is, that’s where the culture is. And you get to be pushed out of your home and experience life there with everybody else and have dinner and just feel alive. It makes it feel very different. Whereas here, you finish work and you come home and then that’s it for the day. It’s a different energy.

IS: And it’s strange, because the thing about Hong Kong is that it still retains a lot of the traditional structures of a village within a city framework. The area where we filmed most of the time was around Mongkok which is largely considered to be the soul of Hong Kong. You’ve got glittering skyscrapers but the thing that makes it different is that it’s also surrounded by neighborhoods and markets. Hong Kong is a series of villages which has been that way since it started and the modernity just kind of sprung up around it. But they’ve managed to hold on to this village feeling which I think is what feels very real and textural. And it’s something that I was drawn to from the moment I first got there. It’s so unique.

And the visual style is so unique as well. Obviously it’s drenched in neon. You clearly have fun with that colour palette. It’s such a opposite from what you’ve worked with, with obviously Goldstone and Mystery Road, using the red of the dirt. This is polar opposite. What was it like to work with all those bright colours?

IS: Well, I was very conscious about the whole thing because I actually integrated an element of it into Goldstone.

Yes, you did.

IS: Yeah. Which I kind of consciously borrowed from Loveland. Yes. Loveland was just a script at that point when shooting Goldstone, and I borrowed elements of Loveland and filtered them into Goldstone so it’s a first taste from that film.

Unfortunately, I feel like I’m about thirty years a bit late for the actual neon because it’s now it’s an LED city. There’s some beautiful old neons that are left. And unfortunately, they’re not given the respect that they should have and they’re slowly disappearing. Because they just draw much more electricity than the LED lights and all these businesses are small scale. And they’ve replaced a lot of the neon with LEDs which don’t have quite had the same kind of atmosphere. But it’s unfortunate that’s the way of the city.

There’s a lot of things in Hong Kong which are disappearing quite rapidly, including a lot of the restaurants that have been there since the Sixties. We’ve managed to shoot in a few of them and so I’m happy to kind of capture elements of Hong Kong on camera. Because even since we’ve shot, a few of the restaurants have been renovated or closed down and transformed into some brand-new plastic kind of ugly thing.

Lifeless.

IS: The whole neon kind of approach is something that when I first saw that energy, part of that was the neon and the LED and the lighting of the place. I immediately just took hundreds of stills. And using the lighting that’s in existence in Hong Kong on the street as the thematic lighting approach, I was conscious of that from the beginning. And working out how to do that, the best way to tell the story.

There’s a lot of technical things to work out as well, this type of lighting. It’s not the easiest thing to film because the light that’s emitted from it is very little compared to when you’re looking at it, when you’re looking at the actual sign which can be very bright. So there’s this balance of lighting ratios which you have to work out how you’re going to do things. And I also integrated a lot of the lighting effects through the visual effects as well which have been influenced from the location.

I’ve read a couple of things where the trailer has kind of reminded them of Blade Runner. But if you look at when Blade Runner was created, Ridley Scott was heavily influenced by Hong Kong and his trips to Hong Kong. And if you look at Hong Kong, if you know Hong Kong cinema, you’ll know that this type of high key neon lighting approach which had the film noir feeling – this has been going in Hong Kong forever, when filmmaking started in Hong Kong. It’s not something that Blade Runner made up, I can tell you that. I kind of see it as to just talk about Blade Runner when you see darkly lit neon images, it’s culturally insensitive.

It is. As you’re saying, there are images there of the laneways which immediately struck to me as images pulled from Hong Kong cinema. Of gang stories, noir stories and things like that. That imagery is so steeped in in Hong Kong cinema. It’s great to see you playing around with that. You seem to have some fun there. It’s good.

IS: Well, I have such a passion for it. And you see some of these old Wong Kar-Wai films or John Woo films and they throw people against those lights. And the thing is in Hong Kong because they have laws there, they allow you to show brands and things on the street without too many legal issues. So that also helps. In Hong Kong, they show real things through their real life, their real presence as opposed to when Hollywood does it. They just recreate everything. And that’s what I really love about Loveland is using this real base and then just adding elements to it. But it’s actually… everything’s kind of real.

It gives a grounded, real feel to it. One of the things which I find interesting about your films is that they’re often about characters who are seeking connection, they’re trying to find their place in the world. And here it looks like Ryan’s character is certainly doing that. Where do you find the interest in these kinds of characters who are looking to see and place themselves in their own worlds or the worlds that they’re forced into?

IS: I just see that as the most fundamental human trait, to seek connection. And we’re all always doing it. Almost every action we do, you can see that the connection that we are trying to connect with our place in the universe, or we’re trying to connect with our immediate people around us or people who are not even close to us. We’re always trying to make some kind of connection. It’s just built into our evolution.

And it’s something that I’ve have always been drawn (to), and Loveland is an extension on that trait. It’s largely about that. It’s about this world and specifically these characters who are struggling against this erosion of human traits which are love and trust, which are part of our connection traits as human beings. And in the world in Loveland, that world is telling us that we don’t need those connection traits anymore, they’re of no use anymore. But the thing is, these traits of connection are something that are hard to let go of.

And it’s the struggle against the erosion of these traits is what I wanted to highlight in a future context, in a futuristic world which is largely an extension of our current world. Places like Hong Kong or China or many parts of Asia. There they are. There’s a lot more competition, extreme competition over there, which we have the luxury of not having here to the extent, not yet, but you know there’ll be a point where we probably will get to that stage. They’re always ahead of us over there. The amount of people competing with each other from a very young age. It’s at a whole different level and that’s something that struck me when I was over there. So how do we connect, keep connecting with each other while we’re actually competing with each other? That’s something I think is the main kind of flow of the film.

That’s really fascinating. When did you edit the film as well? Was it in 2020 that you were doing the editing?

IS: No, we’ve only just finished the film.

It’s quite a long period of post-production and doing visual effects and sound. And there were many stages where I would go back, I would re-edit the film and go back and remix the film on several occasions. Largely because of COVID. There’s just not been this pressure to get the film finished. But you do have to finish it at some point. It was finished not that long ago.

Did the events in Hong Kong and the event of COVID influence how you edited the film?

IS: Well, I think it was. We finished filming in Hong Kong and then the protest movement got happening. I think it was February 2019, March 2019 we finished and then around July, August, this protest movement started to become very active. And that wasn’t really part of the story or anything but I was interested in trying to integrate an element of that. And so I did go back on several occasions and find myself in the middle of the whole chaos with a camera. And it subtly worked its way into the film, but it’s really just a layer. And it’s not really to do with anything to do with the political situation.

And like I said, the COVID time, people have been more flexible about expecting work to be finished on time. It’s just like everything, you know there’s a delay in everything. So I took that opportunity to put more time into the editing and the effects and the sound and the music. I think, I must have recomposed the music… (it) must be fifty times or something. The music’s gone through so many different cuts.

Oh wow. I will say that one of the joys of (an artist like) John Carpenter has been he’s put out a whole bunch of the scores that he hadn’t used. And I will say there’s a part of me that is like, “Ooh I wonder if Ivan’s gonna do that one day,” because I’d love to hear the old scores for things.

IS: We’ve got so much coming. I mean, we actually mixed the music in the film on several occasions. The first two mixes, there was no music or notes from those mixes present in the film at all. And this music may actually end up in another film as well, as a base for another score, because some of it I quite like. It’s a shame, I could use it again.

You do such great composing, the Goldstone score is just next level brilliant. I listen to it so much while I’m doing writing–

IS: Oh, cool.

–because it’s easy to lose yourself in. And it helps you just focus on what you’re doing. But it’s brilliant. It’s really wonderful.

IS: That was the first time I actually gave myself freedom, time and space to concentrate on music. And so when I finished shooting, Goldstone, for the first two months or six weeks, I told myself I’m not going to look at the film, I’m just going to make music. And so that’s what I did. So I had this score before I even looked at the pictures. It actually helped the editing go together really fast because I already had the score completed, a hundred per cent completed.

I want to know about working again with Hugo and Ryan. I love seeing Ryan on screen, and I loved him in Mystery Road and I always get excited when he’s back in an Australian film because he’s one of my favourite actors, and it’s always great to see him working. What was it like reuniting with them both here?

IS: They just really loved the script and what it was about. The struggle for connectivity is something that I know appealed to Ryan, and that losing those traits that make us human in a connected way I think really appealed to both of them. They both came on board very early on. They both liked the scripts, and it was just a matter of locking in the finance, because it’s not the easiest type of film to finance. People are scared of sci fi because they cost so much money and they actually don’t return very well. Not like other genres, like horror for example, where they’re quite cheap and easy to make. It just took a little bit of time to get the finance moving along.

Hugo and Ryan are special actors. They’re one hundred per cent into their career for the reasons of art. They’re not there for the fame or fortune. They’re there because they’re very, very passionate storytellers and they want to tell stories from the heart. And this is why I’m in it as well. And so we find ourselves drawn to each other for those reasons. And the process of making the film is just a joy because we’re all there for that genuine reason. And we just want to make this art that has something to say. And they’re just very, very generous, just one hundred per cent committed.

Ryan and Hugo, they’re just absolutely dreams to work with in every way. And it doesn’t stop there, even when the film is finished, they just said, “Whatever you need, mate, just give us a call. And then I’ll do whatever you want.” You know?

Well, I love seeing you working with Ryan and both Hugo but Ryan in particular because you give him such great roles to work with. His role in Mystery Road–

IS: I mean, Ryan – and he’s done the whole TV thing in America – this is like a bit of a character study for him. It’s a lot of nonverbal activity going on with him. And I think it’s refreshing to see him working this way.

And the thing is it’s the kind of film that really needs to be seen in a cinema. That’s why I really want to push people to get out of their lounge chairs and get into the cinema and watch it because people talk about the difference between cinema and TV, but I couldn’t feel more strongly about this film needing to be seen in a cinema.

Those visuals alone in the trailer, I can’t wait. Do you listen to podcasts much at all? Are you a podcast person?

IS: No. Actually, I don’t think… I’ve listened to one actually,

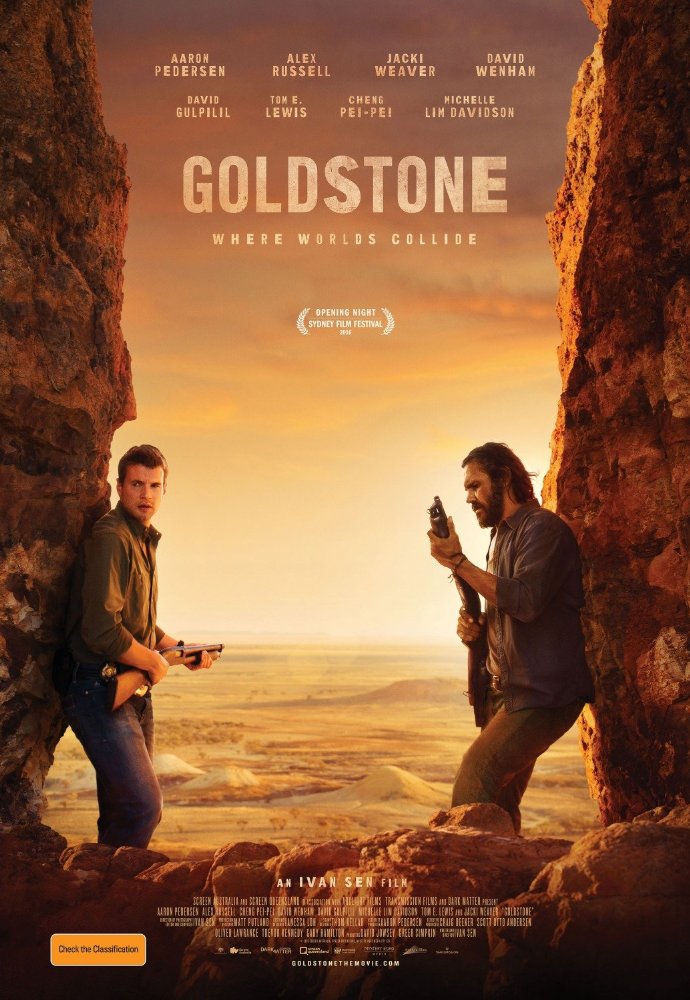

Right. The only reason I say is that there’s this podcast that’s called Screen Drafts podcast. And earlier in the year, Blake Howard and Alexei Toliopoulos who are Australian film critics were on. And they were talking about the best 21st century Australian films. And the gist is they have to rank seven best Australian films. And they both decided that Goldstone was the best of the 21st century.

IS: Really?

Which was pretty impressive. Because it is a great film. And it’s certainly right up there for me. I think it’s fantastic. And I was just curious if you’d heard anything about it or not?

IS: No, no, not at all. But for me, I do have a strong appreciation for Goldstone. I know, it doesn’t go into areas that some people expect it to. But for me, it’s a film that resonates emotionally with me as well as thematically. For me, when I start to watch it, I feel myself just watching, it’s hard to stop watching it. And yeah, for me, if I had to pick one, it is my favourite film up to this point.

I would agree with you there. It’s a film that I’ve revisited quite often. Do you revisit your films often at all?

IS: I try not to. But just by accident, sometimes you start watching things. I think a lot to do with Goldstone is actually also… I mean, there’s so many layers to it, but also, I think Aaron Pedersen grew a lot from making the Mystery Road film. Because he had never made anything like that in his life, you know, where he just gets to walk around and quietly look at things and – without blah, blah, blah, you know. And so I think Goldstone was a chance for him to actually take another step into his craft, into learning about his craft.

Well, you got three legends of Australian film in that film, obviously Aaron, Tom (Lewis), and David (Gulpilil). And it’s the film that I revisit the most of yours that I just can’t escape. It is a really powerful film.

IS: It was really important for me to get those three together. The three of them are iconic. And, they’re not going to be around forever. But this is probably the only time… well, it is the only time that the three of them will be in the one film. I think Aaron might have been in a film with David once before but it wasn’t released (Mimi, directed by Warwick Thornton in 2002). For me, it’s a very special film, I think it was an incredible film to make too, because we made it while living on a cattle station and there was no contact with the outside world. It was amazing.

Yeah, that must be blissful. It sounds nice.

IS: Because the locations are five minutes apart, some of them I walked to from my tent in the morning. Incredible process.

I look forward to watching Loveland and having that comparison in my mind of the different landscapes and seeing how you approach the visuals of a city versus the visuals of the wide nothing. It’s gonna be really exciting.

IS: I’ve got the Gold Coast homing in my cross-hairs as well. So the Gold Coast is going to be seen in a whole different way when I get that going.

Nice, nice. Well, I’m looking forward to that. And hopefully you get started on that next year because I’ll tell you what, the years of waiting in between films is hard sometimes. I know that you got the creative juices and stuff but as an Ivan Sen lover, it’s like, ah, geez, man.

IS: You should check out my Instagram. I just started a couple of weeks ago.

Oh right. I’ll make sure to follow you then.

IS: Yeah, I’ve stepped up partly out of obscurity to… yeah, there’s a lot of stuff on there you’ll probably like.

Cool. I’ll definitely check it out

IS: I’m putting up photos from Goldstone.

Nice. Well, thanks for your time, mate. I really appreciate it.

IS: Thanks for that.