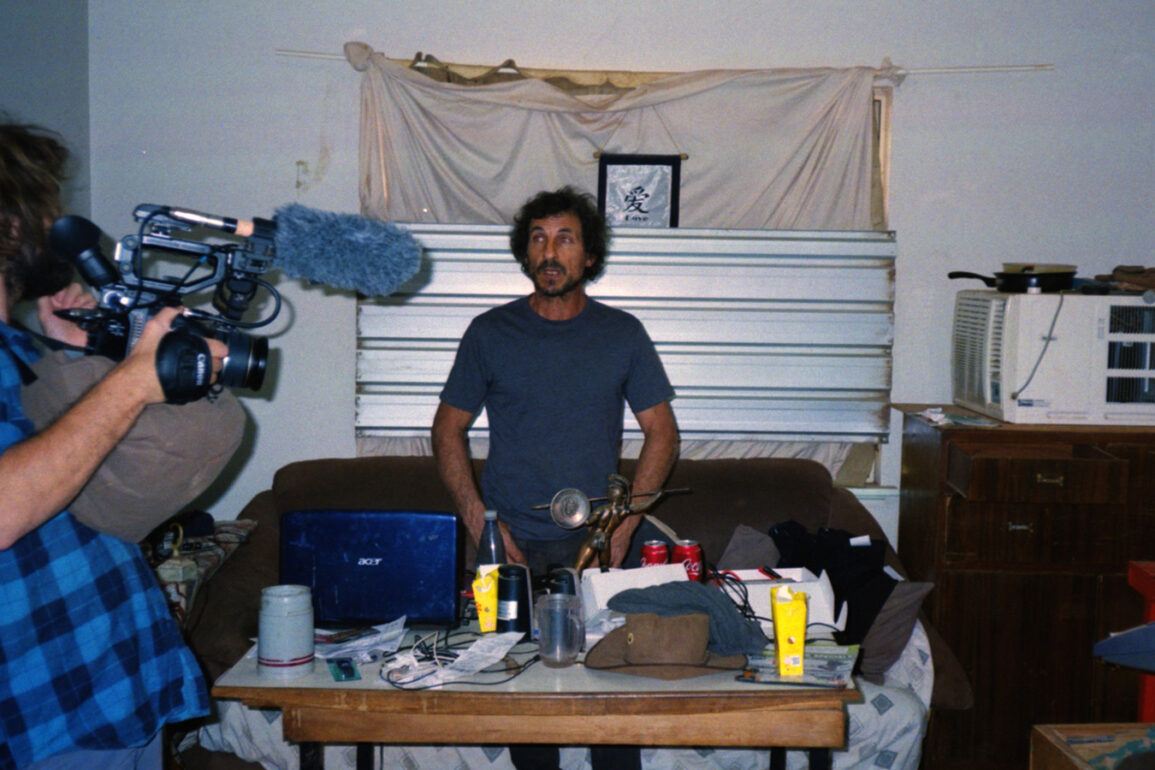

Brodie Poole’s documentary General Hercules portrays the vibrant personality of the Western Australian mining town Kalgoorlie as it undergoes the 2019 mayoral election campaign. Hot in the thick of the race is the titular General Hercules himself, John Katahanas, a true-blue larrikin who lives off the land, challenges authority, and has a grand vision for the future of Kalgoorlie. With a mood setting score by Josh Wilkinson, General Hercules is a magnificent feature length documentary that might unsettle, it might disturb, and it definitely will have you enthralled as it rumbles along.

General Hercules recently screened at the Sydney Film Festival, and will receive further releases throughout the year. If you’re a fan of great documentary filmmaking, then you’re not going to want to miss this one.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Man, what a film.

Brodie Poole: Thanks, thanks. It’s a bit of a rollercoaster.

Oh, I loved it. I enjoyed every single minute of it. I can’t wait to watch it again and just lose myself in it. There are so many characters, and it’s just a delight to be able to watch. Congratulations, you must be pretty proud, I imagine.

BP: Yeah, it is good to see it all together. I like what it does to people, you know? It carries them off away for a while.

Is that your hope when you make a film, that it carries people off in a way?

BP: Yeah, I like that. I was thinking about the film last night. And there’s a lot of space in the film. Like I like listening to long-form music as well, because it puts an audience’s head in the position to encourage thinking of their own essentially. So I guess when I introduced the film yesterday, I also said something similar, like just let it take you wherever you wish to go with it.

How was that screening?

BP: Good. We had a couple. I liked the second screening which was like at the Dendy in Newtown, it was a little bit more intimate and the vibe felt nicer. Premieres are a bit frightening for me with all the snap-snap photography and all that. That was the one that I went for but yeah, the smaller stuff is nice.

Let’s start with the beginning of this story. Because covering the council elections in Kalgoorlie-Boulder doesn’t really seem like the most engaging idea for most people. But what drew you to this story?

BP: Originally I worked on a story with Joe [McLaren], who’s co-producer. Joe and I were living together in Brisbane, and we went on this big road trip to Western Australia because we had a lot of time on our hands really. We both knew that we wanted to tell some kind of story, but we had nothing really lined up. We skipped from place to place. I think we were in Wittenoom for a little bit, which is an old asbestos mining town, and didn’t find a story we liked there, and then went to New Norcia, which is like Australia’s only monastic town in Western Australia. We were like, “Oh, these monks are very quiet. They don’t want to talk to us.” And then we ended up in Kalgoorlie.

And in that hotel room, I found John Katahanas – he does these music covers of a lot of 80s Australiana songs. I reached out to him online to get hold of some of his music, and he gave us like this mud map to his property out in the desert there and we got there. He was a little showman, he played us music for like six hours into the night. He even had circles drawn on the ground where he’d identified that there was gold there and he was like, “I’ll wait till the boys get in, and we’ll dig up that gold and make it a real kind of occasion.”

I spent, I think, three or four days with him on that trip. At the end, he was like “I’m running for mayor next year as well. So you should come back and film that too.” We’d established a friendship at this point, too. Joe and me and John Katahanas all loved to sit in that caravan and enjoy ourselves and have a few drinks. So yeah, we made that plan to come back for the mayoral elections.

It was only when we came back that we realised like, oh, there’s four other candidates, and they’re all kind of interesting in their own ways. And this town is this interesting dysfunctional society that we’re learning to understand. But we only originally had the intentions of documenting what we thought was going to be like a madman campaign or something.

What were the surprises along the way?

BP: We were surprised by everything, really. Also the willingness for each of the candidate who immediately want to divulge everything. Usually with documentary, you work for a very long time to get access. In this case, we rocked up and day one, the candidates are like, “All right, sit down, get this on camera. I’m going to tell you my vision for Kalgoorlie” and were just revealing the world to us. And we’re like, “Nice to meet you.” So that was a great surprise.

The election was interesting, because we got into the election a bit late in the game. We were a little bit behind the eight ball. We were only filming the election for two or three weeks. A lot of the filming happened after the results were announced. I stayed on for three or four months just hanging out with John in the desert a lot of the time. I was surprised to realise the extent of the life that John has lived. He’s a chess champion, he worked at SeaWorld, he was a chef once. He’s bluffed all his way into these bizarre jobs. It was nice to intimately get to know someone like that.

Did you feel like you’d struck gold when you first met him and decided to make a film around him?

BP: Yeah, it definitely felt like there was some significance to making the story. John has this kind of deep poetry about both the way he speaks and his life, observing him as somebody who is out there in the pursuit of gold or like, he’s running for mayor. It’s a beautifully poetic life that he lives. Yeah, it’s like striking gold. Because he’s such a chaotic character, it felt like we were this ride, there was no way to control the story.

I think early on, I rocked up to John some days and I was like, “John, I’d love to get a scene of us on a salt lake prospecting, you know, we have this real kind of moonlight thing to start with.” And John would be like, “Nah, I’m not going to do that. I don’t want to go to the salt lake.” And I’d be like, “All right, well, what are you going to do?” And he’s like, “Well, today I think I just want to fix my bobcat for six hours.” And I’m kind of like, “Okay, we’re making this mayoral election film. I guess I’ll film the bobcat thing.” We definitely had to relinquish a lot of control and roll with things. And there’s some kind of gold in that.

How do you go about relinquishing control? How do you personally do that as a director?

BP: I spent a lot of time out there, I knew that I was always going to be getting things. I can be a very quiet person as well. So a lot of my time with John out in the caravan was just me sitting with a camera on my lap, just me and John, and talking about whatever. I didn’t really ask him too many questions. “What are you doing today, John?” This is what he’s doing. I knew in my mind when there would be a film and when things were significant. I knew some days when he was just changing a tire on his car might not be the most interesting thing for a mayoral election film, but maybe as he changed the tire on the car, he would go into some kind of rant about the election. You never really knew. You just have to be there. And then I think the way the film ends, I was filming the ending knowing it was the ending. I know that I’ve been here long enough now, and I know that this is the ending.

With the other candidates, you’re talking about them being quite comfortable with the camera. How did you get to the point where they understood that this film wasn’t part of their campaign?

BP: The way we made ourselves known to the candidates was “We’re interested in the politics of regional towns and we’re making a documentary.” We gave a very vague idea of what kind of film we were making. “We don’t kind of know exactly what it is yet, but we’re figuring it out.” Given that I present passively, say the Mayor John Bowler was kind of like, “[It] doesn’t matter what film he’s making, I guess I’ll stand up now and I’ll give to you what I deem to be suitable for such a documentary.” People were given a lot of space to decide what the documentary was. Some people are performative. Other people are less performative. It’s interesting to see what people will do when there’s a camera around.

Were there any film touchstones that you looked at as an inspiration for this?

BP: I’m not too sure. I’m not much of a cinephile or anything. At the time, I remember watching that Honeyland documentary, really enjoying that and the pace of that. But it’s rare that I reference other films in the work that I make. A lot of it is trying to use the camera and the tools of editing to match what my observations and thoughts were doing at the time.

Did you do the drone work?

BP: Yeah, I did all the drone stuff. That was behind little alleyways, popping it up, flying it over the Super Pit.

Read Andrew’s review of General Hercules here

What was that experience like? It’s been years since I’ve been to Kalgoorlie so the Super Pit’s probably tripled in size. It is just swallowing that town whole. What does that feel like to capture that image?

BP: To stand at the edge of the Super Pit – there’s a lookout you can go to – it’s pretty surreal because you’re like looking deep into the bowels of the earth. And the whole operation has this humming drone sound of the many trucks turning over. It’s this kind of bassy sound that you feel in your belly kind of thing. It’s hard to grasp ideas of scale as well because the trucks look so tiny and small. You feel like you’re living in this cartoon world, as the general might put it himself. I liked the idea of [using drone imagery to] try to emphasise the scale of these operations as best I could.

Was that when you made the decision, when you saw the Super Pit, to speak to the other townspeople and talk about the history of what’s going to happen with the town? Or did that come through talking to some of the candidates?

BP: Definitely talking to Geoffrey Stokes the pastor raised the stakes. There was a gravity to what he was saying. The blue crosses on the houses and the impending demolition made the talking points of the town not theoretical or hypothetical when you can see this moving machine approaching the community Ninga Mia. Then I started getting interested in the history of the Super Pit. One of the candidates, Suzie, talks about living in the neighbourhoods that were consumed by the Super Pit. One thing we were obsessed with was this idea of an event that happened in time, the kind of finding of gold and there just being this churning machine that is like history repeating itself over and over and over.

You were saying you’ve done road trips around Australia and you’ve been to different towns, looking for stories. Did you find a similarity in Kalgoorlie-Boulder to other towns that you’ve been through around Australia?

BP: Yeah, I think there are similarities. I think one thing that Kalgoorlie does quite well is it’s like a little Simpsons town like Springfield or something. It felt like all of Australia’s hot topic talking points existed on the street. Like we’d sit above the pub we were staying at, looking out from the verandah. And every night they would be like a theatre play out in front of you, like the race relation problems of Australia or the marching capitalism of mining. You’ve got the fly-in fly-out people. Every contentious point existed in this hot pot of Kalgoorlie. And you can find that stuff across all regional towns. But it was a bit glaringly obvious.

Did that excite you when you knew that you had this microcosm in this one town that you could capture?

BP: It was exciting, but it was deeply, probably personally disturbing as well. The film did really affect me. As you’re filming, [you know] this is an important and significant story to tell. But the stories I’m hearing are kind of deeply troubling to me. I was kind of having my own ideologies ripped apart as I was hearing the words of those I’m interviewing for the film. It wasn’t entirely celebratory when I was kind of living and spending time in Kalgoorlie. I was also really sick at the time as well. I had this autoimmune disease that I was getting diagnosed for. I had to fly a friend in to hold the camera for me because I was too weak to hold the camera. I think I lost like 25 kilos or something. So I was going through some kind of nightmare I felt like at the time.

Yeah, I can relate to that, I’ve gone through my own autoimmune diagnosis too. I don’t think people understand what that does to your mind.

BP: It’s strange, isn’t it? Sometimes you’re in pain for consistent amounts of time. And it really does something to you, it puts you in a headspace that you only realise after the event.

How did you keep yourself sane and steady while you’re going through all of the health stuff while also making this film?

BP: My friend Jaydon Martin was the cameraman I got to help me and Joe helped as well. They would take me to Perth, to the surgeries that helped me get diagnosed. How do I stay sane? I don’t think I completely did stay sane, in all honesty. I think sometimes you’ve got to realise that you could be insane for small pockets of time as long as you kind of get out of it at some point. Hopefully I have now but we’ll see.

But, yeah, there were good people around. The general is such a dear friend of mine, and he’s so compassionate. And he has friends in town too. There’s like Kathy who is this real estate agent who took me in to stay a few weeks. It was nice to have these people and there was the skimpy Saffron who was staying next to my hotel room and we’d hang out on the deck after I’d shoot, just talking away into the early evening.

How do you find that balance of being friendly with the people that you’re making a film about and making a film about them?

BP: It’s like an anxiety-inducing question, isn’t it? Because I do deeply care about everybody that’s been involved in the filming process. But at the end of the day, it’s like I take the feelings away and I make a film. My observations are picked out and put on a screen to show people. I’m this judge and jury of how they are represented to the world. It’s something I think about a lot and hope that I do as best as I can. But I let people know that this is what I’m doing. This is what the process of filmmaking is, it involves me doing this. Staying open has been good.

John Katahanas loves the film. His response was, “I see a great future for Brodie Poole films.” And I was kind of “Thank you, John.” And Suzie [Williams – another mayor candidate] likes the film as well. John Bowler hasn’t watched it yet. We sent it over to him. But he was kind of upset with the name of the film being General Hercules. And I think he has this image in his mind that we’ve chosen to put the madman on screen because it sells out cinema seats and stuff, so he’s like, “I don’t think I’m gonna watch this.” But they did sign off saying that he’s enjoyed my company. You hope you get it right. You hope you get your judgments right.

So what makes a Brodie Poole film then?

BP: That’s an interesting question. I try to be as deeply honest as I possibly can. So there’s one [scene where] the general is walking around town, spruiking his policy, but distracted by a lemon tree. I like to leave moments like this in their natural state with very little cutting around this kind of stuff. And even the chronological structure of the film is very much like true to the life. The election result is announced and then the film continues for 40 minutes. I don’t enjoy twisting reality so much. I think what makes a Brodie Poole film is something that tries the best it can to be something true to life.

Is that the draw to ob-docs for you, that true to life experience?

BP: Yeah, it’s interesting. I think this film isn’t entirely ob-doc because there’s so much connection between the subject and me with the camera. I’m very aware of context. The reality is I’m a stranger in this town with a camera. And people in the world are responding to that. Observational film is sometimes very lifelike, but sometimes it feels [strange] to me to not acknowledge that there’s someone standing in the corner of the room holding a gigantic camera. That in itself isn’t an entire representation of the truth too. So I kind of like the interplay between what’s being filmed and the fact that hello, there’s a camera person in the room.

I like that. It’s nice to know that you acknowledge that yes, there is a camera here. Because so often people want to say it doesn’t exist. “Somehow this footage appeared, and I’ve got it and I’ve made a film out of it.”

BP: As if it was plucked out of the atmosphere, those images. Because there’s context for everything, even the racecourse thing. Maybe they think I’m an events photographer. Even the way the news is put together – if you really take a close look at that, it’s kind of incredibly strange. You know, the way someone presents the weather in front of an LCD screen. And we believe it to be normal because it’s what the news is.

I want to talk about the score as well for this film, because oh my god, I loved it. One of the notes I’ve written is that the music kind of squeals almost like a baby on the cusp of wailing at times alongside a metal detector, and it just flows in and out. Can you talk about the creation of the score?

BP: Definitely. It was composed by Josh Wilkinson who is a friend of mine that I met in Brisbane and lives in Iceland now. And a whole bunch of his musician friends. Joseph Burgess was on the violin. I was starting conversations with Josh very early on, and we took rushes to a warehouse and projected them on the wall. Most of the music was improvised, really.

I would bring rushes and I didn’t even really know how to structure the film at this point. But I was like, “Here’s some footage of lava gold pours, hellish scenes, and what can we do for this?” And then Josh would start a demonic guitar thing and then Joseph on the violin would improvise something. When we knew that there was something in one of these tracks that was being recorded, then Josh would take it away and spend a bit more time finessing and adding to it and shortening it because a lot of these session recordings were like 20 minute tracks.

I think you can feel the improvised nature in some of the music. It’s like a jazz track when the newspapers are swinging through the factory. As that one starts, I can hear the musicians chatting to each other, getting everything sorted. That jazz track – I think I was pacing around the warehouse and in my mind, I had an idea for a scene. I’m interested in the way in which information passes about Kalgoorlie. I was like, “Here’s some footage of newspapers. Josh, what do you reckon?” Josh just pointed to the jazz drummer – Caleb I think his name was – and Caleb just started [playing] and then Josh was either like “Speed it up, slow it down.”

A lot of decisions were made on the fly. Even the opening song – that’s an incredible track and it began with a guitarist. I think his name’s Nick. He tuned his guitar so that every string was in mathematical perfect tuning, which is kind of unnatural to human hearing. Like typically a G chord is always slightly out of tune, most chords are, but this had this strange quality and then he kept plucking it in this kind of pulse, and then later Josh would add elements over the top, like some violin and vocals of his wife Yofe in Thai. It was a lot of fun. Even the horse racing scene which is The House of The Rising Sun cover. I brought ten of my friends from Bundaberg around for that, and we were all given hammers, banging on the walls of the warehouses. We had microphones placed all over the joint. Good fun.

What was the choice of choosing that particular song as well? Because it is fairly prominent throughout the film and it’s such a powerful song as well. Did that come from John? Or was it an organic decision to have it in there?

BP: I think it began from when we recorded that fella singing the karaoke song and just got fixated on the idea. Strange things to fixate on, really. In this town, there’s so much happening but I guess we wanted to hold on to some kind of ground. And I think House of The Rising Sun was one thing. We were like, “We can do this, you know? That can be under our control.”

Your film is so deeply about Australia. What does it mean to be an Australian filmmaker right now?

BP: I think it’s an interesting question. I think when I began making the film, I didn’t have a clear image of Australia. I think Australia is this dysfunctional place. And I definitely did the whole ‘going into the desert to try to figure it out’ kind of thing. What does it mean to be an Australian filmmaker now? I think it’s important to realise the absurdity of what’s happening in Australia right now. Because I think Australia is still trying to figure itself out at the moment. And it’s good to be a part of that conversation. I’ve definitely not figured out Australia at the moment, but I definitely enjoy being an observer to the way in which it rolls across.

This film is very much an exploration of identity of what it means to be Australian, in this microcosm of a place that is so distinctly Australian. We’ve got these figures who feel like the poster people of what people overseas perceive Australians to be like, and there’s going to be some really fascinating discussions come out of the film.

BP: I hope so. That’s a big part of the reason to do these things as well. I enjoy people talking.

Did you stick around and chat to people as after screenings?

BP: There were two brief Q&As, they went pretty well. They were good fun.

Were there any interesting discussions that you had with people or interesting observations people had?

BP: I think the film is going to be disturbing for some people. I know a few people have watched the film and potentially are very critical of the film because it in a way attacks authority and everything. I want to see where that conversation is going to go as well. But yeah, it’s an interesting one. A lot of the time people finish watching it for the first time and are put into this like introspective mood. It takes a little bit of thinking.

I love films that do that. I’m a Western Australian myself, so getting to see that kind of side of our WA identity. The FIFO worker is such a prominent thing. It’s how a lot of people think we are. So it’s nice to see that on film and to interrogate that a little bit. I’m excited to see what more people think about it.

BP: It must be interesting. It is bizarre that even I spent years with this film and I feel like I still don’t have all the answers floating in the wind. I’ve got my thoughts about it, but I can still watch it and be confused at points about how I feel about this.

What’s the rollout for it [post Sydney Film Festival]? Because I’ve got a few friends who live in Kalgoorlie who have been asking.

BP: I know it’ll do a couple more festivals in Australia. I would really like to have some local screenings of the film, especially in Western Australia. It’d be such a shame if the film only screened in capital cities, it’d be very against the nature and politics of what I’m standing for. So I’d love to have a local screening in Kalgoorlie and then maybe a bunch of other regionals.