Writer turned documentarian Sean Wilsey debuted his compelling, funny, and riveting debut film IX XI at the 2023 Perth Revelation Film Festival. It’s a curious location to have the world premiere of a documentary about the events of 9/11, but it’s also a decision that makes absolute sense as for an even that shook up and ultimately shaped the world at the turn of the new millennium. IX XI is a magnificent documentary that honours the events of 9/11, while also giving space for the humanity of those impacted directly by the event to breathe.

IX XI sees Sean interviewing a handful of ordinary people who were in New York on 9/11 about their events before, during, and after that day. For some, like actor Griffin Dunne, the day was tinged with absurd moments as he was hounded by a publicist trying to get him to see the latest Children of the Corn film, for others, like Michael Cuomo, it was a day that brought him closer to a realisation of his own mortality than ever before, leading him to rush into a restaurant and order all the food on the menu as a ‘last meal’.

As Sean guides his subjects through their memories of the day, we’re encouraged to reconsider how traumatic events links a society together. For some, the act of terrorism that was inflicted upon New York is almost inconsequential to the personal struggles they were dealing with at the time, such as the impending loss of a mother, while for others, their religion was pulled into the chaotic orbit of the event, ultimately throwing a life of acceptance and assimilation into question.

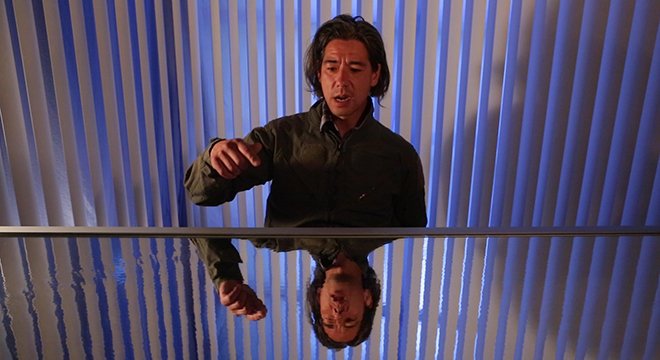

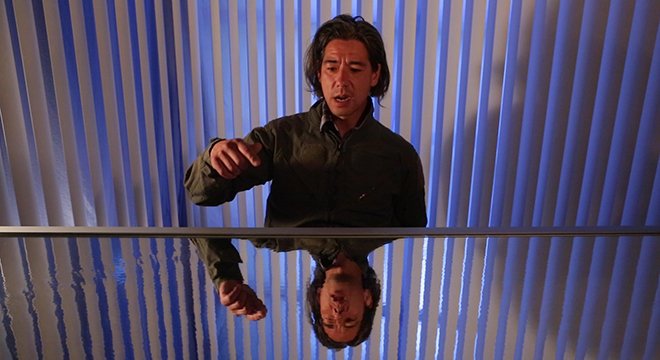

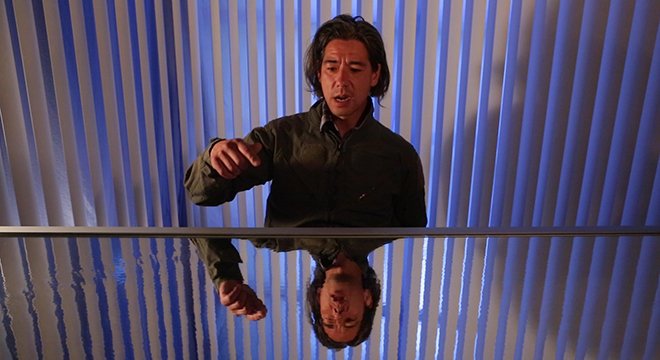

Each interview is framed in a reflective stance, with the subjects either framed by mirrors and darkness, or they sit looming over a body of water that acts as a mirror, reflecting their faces as they sit against a vertical lined background that echoes the familiar façade of the World Trade Centre. This reflection pool also echoes the contemplation and reflection pools of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, a monument that encourages attendees to engage in an introspective look and consider the importance and the impact of that day on society.

While IX XI is a documentary about an event that changed the world in a geopolitical sense, Wilsey ensures that it is a distinctly apolitical film. This is not to say that politics, and by extension, religion, are not factors that inform his subjects lives and memories, but rather that IX XI succeeds in the manner that it reminds viewers that in the moment of a traumatic event, those aspects often slip away, leaving us with the present and the unanswerable question of ‘What is yet to come?’

I met Sean during Revelation Film Festival, where he was present for Q&A screenings during the event. It was after the festival that I caught up with Sean via Zoom to discuss the film and to explore how he approached the subject of 9/11 as an interviewer. Even though I was the one asking questions, through Sean’s approach to providing an answer I was able to see how he manages to put his subjects at ease with during his own interview process. There’s a calmness and a curiosity that comes with Sean’s approach to interviews that reminded me that an interview is more than a series of questions and answers; it’s a conversation that’s driven by give and take, by interest and empathy, and ultimately by wanting to give your fellow person the time to share a bit about themselves in a selfless manner.

This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

I‘m curious about the decision to have your world premiere in Perth. What was the motivation behind that choice?

Sean Wilsey: I’m not a filmmaker, or I wasn’t until now. I published my first book, Oh the Glory of it All, in 2005, and I worked for magazines prior to that in a variety of capacities from researcher to fact checker to messenger. That was kind of my world for a long time. I actually was working on a book when 9/11 happened. I’d sold the book, and I was working to finish it. It was a memoir, and I remember feeling like ‘I can’t work on this anymore.’ Events in the world are way more important and I just can’t do this.

I volunteered after 9/11, and it took a long time to re-establish any sense that my own story had any importance. I have never really fully gotten over that experience. When I started working on this, it kind of came about in an unexpected way where I was with someone who also thought that it was an interesting idea to start interviewing people. It was fun, and it was a totally different experience than journalism where you are sitting down and writing for months or years in solitude.

When it was done, I really didn’t know what the procedure was for getting something out in the world. I had no contacts in that world at all. Writing and filmmaking overlap a little bit, so I knew some people and had people to ask questions to. My friend, the Australian writer Chloe Hooper, has a book about Palm Island and a killing in custody that happened there, Tall Man: The Death of Doomadgee. I worked on an excerpt from that book. She’s working on a documentary now, so I asked her, “Where would you submit this film?” She said, “Try Rev. That’s a really good festival.” I’ve submitted it to a number of places, and Rev was the first place to take it. I thought, “That’s great. Let’s go and premiere the film there.”

There was something beautiful about the fact that Perth is literally the furthest place in the world from New York. I thought, “Let’s start really far away and keep moving closer [to New York].” It’s also really valuable to see what people would think of it there where it’s as far from a personal story in Perth as possible, which it turns out is really not that far.

You’ve been a writer and have now folded filmmaking into your work. Was there a point that you asked yourself permission to make a film? Did you say, “I’ve been a writer for so long, can I even be a filmmaker?”

SW: Oh, my God. Absolutely. I have a lot of respect for editors. Every writer knows that editors can make your work so much better. My way into filmmaking was that I really enjoyed the process. Doing all of those interviews was rewarding and made me feel connected to those people. I felt like I had an obligation to make them as good as I can make them editing-wise. I’ve worked as an editor, so it wasn’t an unfamiliar experience where you take a piece of journalism, and you’ll look at it, “We don’t really need that paragraph. We could jump to this. Maybe let’s start with this.” It wasn’t that different working in a visual medium and that was exciting. I thought, ‘I’ve got to allow myself to do this.’

The aspects of filmmaking that are intimidating to a first-time filmmaker are mostly the technical ones. Every artform has its own jargon and it’s really funny when you start to speak the jargon, “Oh, I can talk about 1080p and about aspect ratios,” but I don’t know what all that stuff means. With writing you don’t work with that many people until the thing is done, whereas with filmmaking you’re working with people from the very beginning, and some of those people are amazing, talented people who are psyched to work with you and share their knowledge. I found a lot of people like that.

It’s not that different from writing in that once you start to understand how something works then all these things are just ways of expressing something. People used to tell me that my writing was very cinematic, and so maybe that made me feel like I had a little bit of a right to try cinema, because I did understand what they meant. I did always write things that were very visual, and you could really see what was going on.

When you’re seeking out people to interview, how did you cast your net out to ensure you had a group of people who had a shared experience like 9/11?

SW: I did a couple of anthologies, and that experience of putting together an anthology was similar [to this]. I did one about the fifty states, it was fifty writers on the fifty states, State by State: A Panoramic Portrait of America. I did that with my friend, Matt [Weiland], we co-edited the book. You know that you can’t have fifty of one type of person writing about the fifty states. “Oh, yeah, let’s get like fifty white male journalists to write about the fifty states.” That’s not going to go over. It’s the same with IX XI, you could get an articulate person to tell the story of 9/11, but if you get ten people like that, it’s just not going to have the texture that you want.

I have always felt that the nicest thing about New York and the thing that keeps me in New York is that you’re always interacting with a variety of people who have their own stories and see things in a in a different way. One of the people in the film, the UPS guy Kevin, I met at a garden supply store. I was there to find out how to take care of a bunch of palm trees that somebody had given me. They weren’t huge, but they were real palm trees. Somebody that I knew had found them on the street because they had been put out on the sidewalk. I have a pickup truck, so I went and picked them up and then realised, “Oh, God, I’ve gotta take care of these.” I went to a garden supply store and Kevin was there. He’s a friendly guy and we just started talking. I described my trees, and he was like, “Wait a minute, where did you get those trees?” “They were on 28th Street.” He said, “I know those trees. I used to take care of those trees. They were in a nightclub, and it closed. I used to take care of him in the daytime.” I said, “Well, do you want to come over and have a look?” He said, “Sure.” We became friends and just started hanging out.

That’s not even that unusual story because you’re always a pedestrian in New York, you’re always walking around [meeting people]. Most of the people in the film were not people I knew. In fact, the only people I knew prior to shooting was the guy from The New York Times and Griffin Dunne. It was kind of a healing experience to get to talk to different people about 9/11 and feel like not everybody had the same take on it at all. For example, the actor who lost her mum 9/11 had no relevance whatsoever except that it coincidently overlapped with her realisation that she was going to lose her mother. I met her on a subway train. She was with a kid who she was babysitting, and that kid knew my kid and we started talking. I thought she was interesting. I ended up interviewing loads of people in it, and not using all of them.

We’re talking about enjoying the interview process. It’s the thing that I enjoy the most as I find that as you get to find about how they live their lives, or about the work they’ve made, gradually over time the more that I do, the more their stories become part of me. I’m curious for you, having interviewed so many different people, and specifically about 9/11, how that has changed you?

SW: My first impulse was to say, ‘I think it makes you a better person.’ Then I thought, what does that mean to be a better person? A lot of conversations can just be waiting for someone else to stop talking so you can say the thing you think is so interesting that you want to say. When you’re talking to people, it’s profoundly rewarding to try to understand their perspective. The best moments in the film were when people didn’t think they were going to say what they were going to say. They really are surprised, and you’re surprised and you’re having that moment together. It’s a moment of discovery with another person and that’s something that you cannot have by yourself or if you’re planning what you’re going to do or say, and it’s extraordinary.

Michael Cuomo, the guy who had that crazy last meal, had never talked about that before. I don’t think he would have talked about it if he hadn’t felt like the feeling between us was a trusting one. I think everybody felt like a real sense of trust and that we were there to just explore something together and that the film had zero agenda, which it does. There’s no agenda other than ‘let’s try to comprehend what this event might have meant outside of the almost overwhelming pressure to see those events in in a political or ideological way.’

The first screening was interesting. The U.S. Consul General came to give a welcome and talk about 9/11, and there was a guy there who jumped in saying, “What about Ukraine? What about Afghanistan?” It wasn’t entirely clear what his point was, except that he was pissed off at the United States. Which is like, of course, why wouldn’t you be? But that wasn’t the point of the film.

I was really thrilled that the U.S. Consul General came because I knew she was going to be watching a film that looks at the event in a different way. I thought, “What is she going to think after watching it?” It’s not a pro-American film. It’s not an anti-American film. It’s not even a film about nations in any way. There’s one moment about ‘Are you proud to be an American?’ It’s important because it’s at the end of the film and it’s a film that hopefully makes you ask questions. At the end, she clearly enjoyed it and it had been a good experience for her. The protester guy had stayed for the whole film, and evidently, had changed his opinion, because he didn’t launch back into the same sort of diatribe that he’d begun with. I thought, “Cool, that’s what I want to have happen.”

At the second screening, there was a man who had asked a question, and he had been a member of Navy SEAL Team One. Clearly that’s a group of people who experienced the aftermath of 9/11 in a very particular way. He must have come to the screening in the purist way, where he must have seen it in the programme or something, or maybe he’d heard the radio interview I did a few days before. I loved that he was there and that he’d watched it. We talked for a little bit after the film, and he was asking me more questions. I wish I’d actually had more time. It was significant to me that he had come.

As you suggest, this is not your typical 9/11 documentary. It’s not the image of the planes hitting the building and the towers collapsing continually. That is in there, but it’s also not about that traumatic experience entirely. What does that mean when people come to it and maybe have that preconceived notion that it is going to be all trauma and tragedy, and then they watch it and see it’s something else?

SW: It’s about what we were, what we were left with, and what we were after. As you say, that moment is in there. For a while, I tried to never include a single image of that happening. I didn’t stick with that as an idea, but earlier drafts of the film didn’t have that because I really didn’t want it to be about that. But I also realised you should see it. It is important and the clips of it that are used are directly connected to something someone is saying or were shot by somebody who we were listening to a story about. I think that one shot that Evan Fairbanks did, where he just happened to be down there and he says, “Can I take one of these cameras?”, despite it being a very pivotal document, it’s not the one you always see. It’s still not an overly processed image of the event. The one you always see is further back of the whole skyline, one building is smoking and it’s more about the guy that’s right in the foreground of that shot who’s still trying to go about have a normal day. You can see that guy looking down, trying to act casual and it’s his reaction that is so moving.

The thing that you don’t ever think about is that prior to the collapse of the towers, there were people who were killed by all this falling debris. That’s not ever really discussed. They’re not really what we think about or talk about. I remember when the first [tower] got hit, like Colin the journalist, we all thought, ‘Well, there’s going to be a big fire, but they’ll put it out.’ You didn’t think the building was going to come down. I remember thinking when it did come down, ‘Well, I guess now we’re just going to have one tower.’

It’s those moments where you’re trying to catch up with reality that are interesting. They reveal a lot about your own state of optimism. You rely on your own inner resources to apprehend the meaning of something before it becomes obvious or we all agree about what it means. Maybe that’s the most interesting thing, there are categories of opinion about 9/11. There aren’t so many individual opinions about 9/11, because an individual opinion would be about yourself and your own experiences. We have collectively fallen into ‘9/11, we had it coming,’ or ‘9/11 was absolutely the most tragic and unmerited thing imaginable,’ or ‘It was an inside job,’ or whatever people like to think. It’s not about your own day or your own experience, usually, which is much more relatable.

As you’re absorbing these stories about people who have experienced something the same event that you experienced, how did you keep your own perspective and memories of the day separate from what you were hearing? Did they distort or change them over time?

SW: I got a friend of mine to interview me for the film because I had a story that was, in some ways, the catalyst for wanting to find other stories. As soon as I saw the interview, I thought, ‘There’s no way I want to be in this film at all.’ My story was that I was trying to get internet in my house, because I had dial up and I wanted to get high speed cable with the big company that provides that service in New York, Time Warner. They’re the worst. Everybody hates Time Warner. They kept sending technicians to try to get it working and they would make you stay in your house between like 7am and 9pm, a ridiculous window, and they would show up just when you were trying to get some lunch or something. They couldn’t fix it because, as they eventually explained, they didn’t really want to fix it. “We just want to show up and have it known that we were there because we have a quota.”

Finally, this guy said, “Okay, I’m going to fix your problem but can you please write a letter to the head of the company and tell him that I did because I’d really liked to get a full time job here.” I said, “No problem.” He got it working and I wrote a letter to the head of Time Warner where I excoriated Time Warner and praised this guy. As a writer, you’re like ‘I’m really finding my voice here. It’s a really good letter.’ On September 10, I had been out skateboarding, and there was a big rainstorm and I got totally drenched to the skin. I got home and there was an answering machine message on my machine, I hit play and a woman’s voice with a super New York accent says, “The President would like to speak with you about your letter.” I thought, “What does that mean? The President?” And then there was another one, “The President is very eager to speak with you about your letter.” I thought, ‘Oh my God, I get to talk to the head of Time Warner and he knows what I think. I thought maybe I could make a difference. That was due to be Tuesday September 11, we were to have this conversation. That conversation never got to happen. Of course it didn’t, and the idea that it would was, like so many things, immediately absurd.

I thought, ‘I wonder if other people have got stories like that.’ Of course, the stories that I found were more moving and interesting. It completely changed how I thought about it. My favourite story might be the Muslim girl who was just consumed with persuading her father to let them move back to where they finally felt assimilated and comfortable. She said she had this victory, and I love that line because it’s coming from a Muslim woman in a hijab and it’s about something totally different than the victory that people who sympathised with the terrorists might have felt like they had. It’s the inversion feeling and you end up experiencing the emotion and the loss. My story is just a purely funny story, but the ones that are like tender and plaintive reorder the way you think about that event and about life in general. Those are the moments that are worth it.

For me, the story of the final meal was the one that broke me and felt very relatable. It felt like something that we are all going to do eventually but having that immediate notion to go ‘I’m going to sit down and order right away and try as much food as possible before the end comes.’ I was crying as I felt seen, and yet I felt like laughing at the same time. It was a cacophony of emotions.

SW: Absolutely. Totally a cacophony of emotions. It’s funny, because I was reacting and laughing so much to the story as he was telling it, which I think made him tell the story better. But my God, he walked out of the restaurant with a bottle of champagne!

That comes back to the interview process which is reacting to emotions. It’s not just placidly sitting there and absorbing somebody’s story and waiting for your moment to ask the next question. It’s an emotional conversation, right? The feeling I got from the film was that people were sharing their genuine emotions and stories with you. There’s no artifice to it.

SW: You’re really making me go back and feel it again. That’s my favourite moment in the film, and you couldn’t get to that moment without loads of other moments, of course. I remember some of the interviews were lengthy, but none of them took longer than a day to do. I never had anybody come back for a second day. Some of them would start in the morning, and we would go all day. We would break and have a meal. I felt at the end of nearly all of them almost like I was empty in a very satisfying way. I can’t think of another interview experience [like it]. Writing is also different because even if you’re recording, you’ve got to take a lot of notes and you can’t fully surrender yourself to the encounter you’re having with the other person. But in this case, I thought, ‘It’s all on the camera. We don’t have anything else. There’s no point in me taking any notes.’ Occasionally I would think ‘I might want to contrast this with something that happened in another interview,’ and then I would take a note, but usually I was some kind of vessel to interact with the other person and then I would feel completely emptied out.

I remember sleeping really well, and having crazy, interesting dreams. I’ve stayed in touch with all of them. I ended up feeling like – and this is sort of an odd thing to say – I’d made a little family with all these people. That was a really satisfying experience. I felt a lot of love and affection for all of them.