Sara Kern’s masterful family drama Moja Vesna is wrapped around an engaging and powerful central performance from newcomer Loti Kovačič. Lev Predan Kowarski’s cinematography embraces all the perfomers, but rarely leaves the presence of Loti’s Moja (Moi-ya), with the newcomer giving one of the most powerful and soul-wrenching performances by a young actor in recent years. As Moja’s sister Vesna (Vez-na), Mackenzie Mazur is equally entrancing as a soul adrift in a sea of sorrow after the death of their mother. Equally adrift is their father Miloš (Gregor Baković) who manages to feed and house Moja and Vesna, but finds it hard to navigate the additional impending life change that is awaiting the immigrant family: Vesna’s late-stage pregnancy that she almost entirely ignores the notion of it occurring.

The subject of loss and grief looms over Moja Vesna, as it has done in Sara Kern’s previous short films. And while the immediate notion that this would be heavy going for audiences is hard to escape, the presence of Claudia Karvan’s empathetic stranger Miranda and her whirlwind daughter Danger (a joyful Flora Feldman) occasionally adds a welcome levity to the scenario. As Danger and Moja find ground for a friendship, the malaise that Vesna struggles to escape threatens to break that bond.

In this interview, taken in the midst of the Melbourne International Film Festival, Sara talks about the themes of Moja Vesna, while also exploring her work practice of working with younger actors. This is the first Australian-Slovenian production, and Sara talks about the importance of telling a migrant story within Australian cinema.

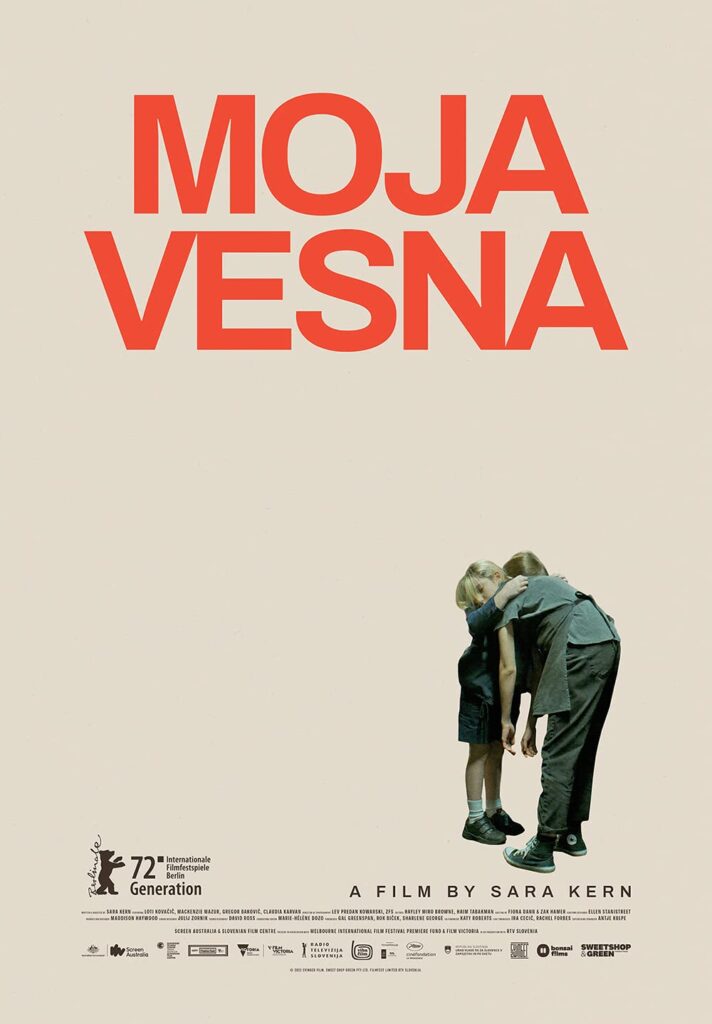

Moja Vesna premiered at the Berlinale’s Generation Kplus program, and is a MIFF Premiere Fund-supported feature.

First of all, thank you very much for your time. And thank you very much for your film as well. It is a very powerful, very beautiful film.

Sara Kern: Thanks so much.

I was very moved by it, mostly because of the central performance from Loti [Kovačič]. That is just one of the best performances I’ve seen from child actor in a long time. How did you go about finding Loti and the direction that you gave her to be able to give Moja the depth that she needed?

SK: Working with children is something that I’ve been involved with for quite a while in short films, and before moving here, when I worked at TV Slovenia’s children’s programme. I realised that there’s just something about working with children that I enjoy. It is a slightly different process in the way we work together to find these characters with each of these children, but yes, it was a natural progression for me to write a feature film told from the child’s point of view.

We were casting for Moja for a long time. We were looking through the Australian-Slavic communities because I was hoping for someone who’s bilingual, and can speak one of the Slavic languages. I wasn’t even hoping to find someone who’s Slovenian-Australian, because the Slovenian community here is so small, because the country is so small. It was an incredible amount of luck we found Loti. She immediately caught our attention, her presence on screen and her sensibility are so captivating. And she has no prior acting experience. She’s into soccer and coding, and stuff like this, but she was keen to get involved and even though she was nine at the time, she took our work very seriously, and this shows on screen. We spent a lot of time together, doing improvisations and chatting about the character and finding out what the differences are between her personally and Moja. Getting to know each other and building mutual trust was very important, so she knew she could tell me straight away if she had a problem with something or didn’t feel comfortable in the scene.

I didn’t share the script with her because I wanted to keep things a little bit fresh because we were shooting for 25 days. I’ve had all these experiences working with children, but it was maybe five shooting days for a short film that was the longest period that I’ve worked with someone. So 25 days, I was anxious about how she was going to go, but she was so good. I think it helped that I kept explaining the story as we went along. We’d discuss before each scene what’s going on and what her lines were, so she didn’t have to learn anything in advance. We mainly worked on getting her into the right emotional state and being able to really be present in the moment and respond to the other actor in the scene. Loti and Mackenzie Mazur, who plays her sister Vesna had such amazing chemistry from the first time we put them together in a room, and I was so excited about this that I went and rewrote the script with Loti and Mackenzie in mind specifically. I added tender scenes between them which I find are crucial in the film now, and they were not even in the script before Loti and Mackenzie came on board.

She’s just very powerful here. And of course, Mackenzie [Mazur] and the rest of the cast is very great too, but the film does hang on Loti’s performance, and she does such a great job. Your work is quite focused on mortality and death and grief, and I’m curious what the draw is in exploring those themes on film?

SK: I think it’s probably got to do something with my childhood. So far, in my short films, and in this film, I’ve drawn heavily on my experiences growing up. I’ve written these fictional narratives out of something that was very real, from the emotional landscape of my childhood and the family dynamics I knew very well. There was much grief in my family, and largely unprocessed grief. I was this ‘mature’, responsible child, like Moja is and people saw this as a good thing, a positive thing, but in fact, it was a coping mechanism. It was my way of securing closeness with the adults around me, it was my way of getting what I needed as a child. And it distracted me from my own sadness. This can be a big problem later in life, so I wanted to find a way for Moja’s character not to do that, and explore how she can get, by the end of the film, to a place where she can allow herself to be present to her own emotions and not have to let that part of her be split off.

I just find grief so endlessly perplexing. It’s such a complicated emotional state. And I think every single experience of loss is different for every single one of us. So it’s hard to make any generalised statements about it or to write one story and say, “Okay, that’s it, I’ve dealt with that topic.” As you dive deep, deeper and deeper into it, it offers more and more layers, and I just find something about the nature of it, that is so contradictory. You expect that you’d be sad, and you’d be crying a lot when you’re in grief, but then you find yourself laughing uncontrollably or suddenly being very angry, and there are all sorts of things that one can go through. I just really wanted to explore that through this story and show how one family tries to navigate this experience of grief; how each one of the family members tries to find a way to live with their loss. How to find enough light to be able to live with the sadness. It is perplexing to me where we find this light, this determination to go forward, this strength to live on.

I think it’s trying to make sense of something that we all go through at a time in our lives. And as you are saying, we’ve got these three main characters who are all dealing with loss and grief in their own different ways. There’s a moment which I thought was just so powerful, and very complex, which is when the father, Miloš, puts on his wife’s slippers, and Moja is standing there and he sees her looking at him. And he says, “I don’t know why I did that.” And to me in that moment it felt like he was saying to himself, he didn’t know why, but then on the same hand, there was almost this envy, “She’s gone and I’ve got to deal with everything.” And there is this emptiness left. I don’t know if that’s something that you were exploring there or not, but that’s how I read that moment at least and it just goes into the complexity of how we all deal with grief in so many different ways.

Can you talk about the different moments where each of these characters are dealing with grief? And focusing on how they explore grief in these moments of sadness? How important was it to have those moments in the film?

SK: It was crucial. The film is built on these details. It’s this less is more approach where I’m drawn to exploring these little mundane things like the father putting on those slippers. It was really nice hearing how you interpreted this. I was hoping for that, for people to turn a small thing like this into something bigger and more significant. And, like I said before, the nature of grief is so surprising sometimes, you find yourself doing things that are quite strange. I see this moment with the slippers is like that. It’s unconscious, I guess, you find yourself trying to work something through. And you find yourself doing all sorts of things to get there.

Vesna very much does that throughout the film. Maybe she’s the most active in this way, she chases death. She almost tries to become her mother in a way by doing all these self-destructive things, because she’s looking to work something out—to understand her mother by following in her footsteps. In a way, she’s trying to get back to her mother or trying to address something in their relationship which remains unspoken and keeps returning to haunt her.

The set design of the house, it feels it’s quite a deliberate choice to have all the things there in the house. And to me, it feels like it reflects who Moja is as a person, that she’s been forced to step into the role of being a carer and the house that is around her has forced her to age rapidly. I’m curious if you can talk about the production design and the set design of the house and how you use that to reflect the themes of the film?

SK: A lot of the story is set in the house because the family is closing in on itself a little bit. It’s this unrenovated rental that they live in, so the house feels a little bit claustrophobic. I just wanted to create a sense that they’re closed in because I find that’s another thing with grief, it can be so profoundly isolating.

And then when you’re a migrant, and especially a migrant from a country that is so small, and having this language, Slovenian, that almost no one else speaks, it can deepen the sense of isolation and I wanted to show that they’re almost an island. Moja and Vesna, in their own ways, they’re both trying to find a way out of this house.

Another thing that I wanted to show is that the family lives in this small house while at the same time they’ve got this bedroom that they’re avoiding—the bedroom where the mother’s bed is, with its bare mattress; it’s like a room frozen in time, a room devoid of life that sits right in the middle of the house, like a hole in the heart. The father is sleeping on the couch and the girls have got a bunk bed and there’s clearly not enough room. So it’s like the mother is still taking a lot of space or maybe has begun to take up more space than while she was alive. There are other things around the house, like the chair where the mother used to sit, which Moja now caresses and worships in a way. Vesna keeps trying to destroy these sacred objects as a way of trying to force the family out of the status quo that they’re in—even though she’s the one who’s literally chasing death throughout the film, she’s also the one who tries to force life back into this house.

As you’re saying this is a migrant story, what does it mean to be able to tell a migrant story in Australia today?

SK: Oh, it means so much. I’m quite humbled by the whole thing. That we managed to even get the funding for it and shoot it and finish it. It feels special of course because it’s my first feature, but it’s also the first ever Australian-Slovenian film. So to see my home country represented in an Australian film, it’s quite special. It felt like that was the most honest perspective or the perspective that I felt the most comfortable in to set my first feature in this migrant story. Of course, they had to be from Slovenia because I’m from Slovenia. I’ve lived here for eight years and like I said before, I drew heavily on my childhood experiences in Slovenia, but I was also drawing from my experiences as a migrant here. And it’s just amazing to be able to combine those two into a story.

The last question which I want to ask is about the presence of poetry in the film, which is really quite beautiful. And it really feeds into how Vesna deals with grief. How important was it to reflect the poetry in the visuals of the film? It is visually poetic film, too. And I’m curious how the relationship you built up between the two went about?

SK: The slam poetry was incredibly important to me from the beginning. Although I had different poetry in there at the script stage, which worked really nicely. I thought it was perfect for the script, and I was happy with it. But then once we cast Mackenzie, who really brought something so unique and raw to the role of Vesna, we started rehearsing the poems, and it was fine, but it wasn’t 100%. I didn’t believe that it was really her slam poetry, you know? And so then we kept talking and improvising and having rehearsals and then she just started writing her own poetry during rehearsals.

Then rehearsals became more and more just us doing slam poetry. So she’d go home, and she’d get into the character and write all this slam poetry and come back and then perform and we talked about it. She ended up writing all of it herself, so that was pretty special. And as I said, I like to find a unique way of working with every single one of the actors, and with Mackenzie it revolved around the poetry, and that was the main anchor for us during the rehearsal period.

There’s just something about slam poetry that I really love and I wanted to have it in the film as a contrast to the silences and all the unexpressed things andthe family’s general inability to communicate. I think Vesna poetry is really her way of distancing herself from the family and trying to find a way to express herself. She’s trying to find a way out in some way. She’s articulating something that she is unable to say maybe to her father or even to herself. She’s found her way of saying the unsayable, which then also helps Moja to finally start to talk about her own loss—and feel whatever emotions saying these words brings up in her.